Using co-creation to study gender fair grant allocation

By Helene Schiffbänker (JOANNEUM RESEARCH)

Posted on February 24th 2022

Starting point

The GRANteD project analyses if and where potential gender bias occurs in grant allocation on a general level, but also in detail in five European research funding organisations (RFOs). The analysis of each RFO covers gender bias risk assessments of policies, interviews with RFO staff and panel members, or observations of panel meetings, as well as a linguistic analysis of evaluation reports and applications.

For our research, RFOs are highly relevant stakeholders, and at the same time, they are experts in their field. In GRANteD we aim to make use of the knowledge and experiences of these practitioners; we perceive them as partners in our research, as co-creators for new insights and knowledge. Representatives of RFOs are especially relevant to involve when it comes to fine-tuning research questions, reflecting on first research findings, and developing tailored recommendations for further policy design.

To realise this co-creation approach, we have established the GRANteD Stakeholder Committee (StC). Now, we aim to reflect about this part of the GRANteD project and invite the readers to provide their own experiences with co-creation between researchers and practitioners. We argue that when working with stakeholders both, research evidence and practitioners experience is significant.

Co-creation

Co-creation refers to a joint partnership-oriented creative approach between two or more parties, especially between an institution and its stakeholders, towards achieving a desired outcome (van Westen and van Dijk, 2015). Bajmócy et al. (2019) point out that co-creation means equal partnership of diverse stakeholders and the reflection of existing structures and power relations. Participants interact on an equal basis. “Emphasis is placed on creating conditions of equality among the different stakeholders involved in the creative process: the contributions of the different co-creators are equally valid” (van Westen and van Dijk, 2015). It is a process of shared making in which values, ideas and assumptions are made explicit.

Co-creation is a process, driven by various stakeholders from different backgrounds and expertise, aiming at creative outputs. It is crucial to use all co-creative capacity, defined as ‘the deep involvement of a range of key stakeholders across scientific, governance, and local practice boundaries to create the infrastructure and context that enables and sustains the use of evidence in practice’ (Metz and Bartley, 2015, p 334). Thus we see co-creation as a collaborative process that enables the generation of practical knowledge by sharing experiences between various stakeholders.

Co-creation in GRANteD

For the GRANteD project, the co-creative approach appears beneficial in two directions: Firstly, co-creation serves as a distinct method for engaging stakeholders around the research topic, in this case gender bias in research funding, and for bridging stakeholders’ experiences and needs in this area. Co-creation can thus facilitate building successful partnerships and exchanges between RFOs. Secondly, by drawing on stakeholders’ experiences, new knowledge can be created in a collaborative manner. This helps closing the gap between research and practice, between research projects and RFO practitioners responsible for designing and implementing policies. Empirical evidence generated in research projects should enrich and provide a better fit for policy design.

It becomes clear that research findings need to be more closely linked to practice, when we look at the implementation of gender equality measures in research funding. On the one hand, there is a broad range of research findings on gender biased outcomes of grant allocations (Wennerås and Wold 1997; van den Brink 2012, Madera et al. 2018; van den Besselaar et al. 2018). On the other hand, various regulations and policies to increase gender fairness have been created and implemented at national or organizational levels (see e.g. Cruz-Castro et al. 2019; EC 2009; EC 2016). Yet, the very implementation of policies and measures is a complex task, and for gender equality policies, feminist implementation studies have identified several challenges (Caleo and Heilman 2019; Carey et al. 2019). We still know too little about the effects and impacts of implemented measures. Some RFOs have been involved in discussions about gender bias in grant allocation processes for decades, but to what extent the policies aiming to mitigate gender bias are effective and able to overcome gendered structures is often still difficult to measure. Impact indicators are rare, need to be further developed and applied systematically. Studies have shown that the implementation of gender equality policies in organizations does not necessarily guarantee that they would be implemented and realized in the intended form (Van den Brink and Benschop 2012).

Further, RFOs and other funding bodies need capacities for designing and implementing gender equality policies. Those include not only personnel and other resources but also awareness about where and how gender plays a role in the grant allocation process, and know-how about translating general gender equality objectives into practice (Callerstig 2014). How this gender and change knowledge is established and shared between individual actors and how it becomes collective organizational knowledge has just recently been studied (Van den Brink 2021).

Thus, implementing gender equality policies is a challenge that varies between different RFOs, depending on awareness, resources, know how within and across the organisation. The complexity in which policies are embedded and potential risk factors for the implementation have been illustrated for the five RFOs participating in the GRANteD project in a policy analysis report (Husu and Peterson, 2022).

Therefore, it is relevant for GRANteD research to create an overview of what RFOs have done already, going beyond mappings, providing insights into the practical experiences and the motivation for implementing the selected measures. Hence involving RFOs as stakeholders and as co-creators in the research process seems an appropriate approach.

RFOs as co-creators

Against this background, it is our starting point that the co-creative approach could support and improve the design, implementation and assessment of gender equality policies in RFOs. The participatory and co-creative methods seem promising for generating more need-driven research results and tailored recommendations, and thus support institutional change in RFOs. By this co-creative approach, we aim to increase the practical impact of our analysis and facilitate the exchange of experience between RFOs regarding research and practice.

By strengthening the role of RFOs as stakeholders in the research process, we expect to provide more inclusive and sustainable results and better address societal challenges (Loveridge and Saritas 2009). Many funders are constantly working on improving their policies and services, which means reflecting, considering, designing, implementing and evaluating new policies and instruments to foster a (gender) fair grant allocation process. For public RFOs, national policies and steering from the Ministry or other national body may include accountability and guidelines on gender equality. Beyond this, RFOs are internally observing and evaluating their processes. Additionally, applicants, external reviewers and panel members provide feedback on RFO procedures, as do research performing organisations (RPO) and scientific societies. RFOs are constantly collecting and reviewing a variety and large amount of data across the funding cycle and by this, gain ideas about how to improve processes. All this information can inform the GRANteD research.

Aims and benefits of a co-creative approach

A first aim of our co-creative approach is to make policy design more evidence-based and to use co-creation to make research findings more robust and sound, by providing evidence for policy design and further organisational change. As a result of building teams of researchers, practitioners and sometimes policy makers, various funding related topics can be explored from a transdisciplinary, trans-organisational perspective. It is further important to better understand the context and culture of the various stakeholders collaborating with the GRANteD project and to value their expertise. This understanding is deepened by individual interviews we are conducting with selected stakeholders in the GRANteD project. Information from interviews may be crucial for the interpretation of research data. In addition, stakeholders’ feedback on preliminary research findings is valuable for GRANteD research as well. Here we aim to create space for new ideas and reflect diverse perspectives.

A further strong motivation for our co-creation approach is to include those who could benefit of our work, because our recommendations at the end of the GRANteD project indeed should reflect their needs. The GRANteD project is – at least partly – able to pick up some questions and needs of RFOs and integrate them in the various data collection instruments, like the surveys sent to the RFO applicants or the interview guides for panel members. When newly implemented instruments or approaches are integrated in the applicant survey, RFOs receive prompt feedback from applicants and first data on and insights into their newly implemented policies. This was the case for two of the RFOs which were part of GRANTeD research, Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), concerning the recent inclusion of a narrative CV into the application documents. At the same time, involving RFOs closer in the research project helps to raise awareness of gender bias in RFOs. This takes place when members of RFOs are asked to provide data for the GRANteD analysis; then GRANteD researchers need to explain the research design and why each data is relevant for the overall analysis.

A further aim affects stakeholders who may benefit of collaboration not only with the members of the GRANteD project but also between the other stakeholder partners involved in the GRANteD StC. When RFOs aim to develop new gender equality measures, they might have some detailed questions to be discussed with other RFOs. Some but far from all European RFOs have existing national or regional networks to discuss gender equality measures and policies with peer RFOs. In the GRANTeD StC they get the chance to learn from each other and exchange knowledge by establishing fruitful and sustainable collaborations. Topics of concern can be discussed, and experiences and knowledge be contextualised for each organisational setting. To make it easier to get to know each other and to develop mutual trust, meetings of the GRANteD StC were scheduled more frequently than initially planned. Within these meetings, small breakout rooms were provided, which supported informal communication. Here more experienced RFOs shared experiences with organisations which are only starting their gender equality activities and who – by their tailored questions – were able to stimulate the exchange of experiences. By sharing ideas about good practices, about success factors and pitfalls, RFOs provide mutual inspiration for what can be done. This informal information may be crucial for the implementation in practice. The exchange of expertise and experiences is expected to empower StC members, in particular when they are agents of change, implementing new policies and organizational change. Furthermore, the exchange also contributes to our knowledge of divergent approaches of RFOs regarding gender equality and various challenges they are facing.

A final aim of our co-creative approach is to emphasise the importance of sharing and disseminating the research findings and recommendations to other RFOs and finally also more broadly to the scientific community. Stakeholders’ participation in the GRANteD StC should increase their gender awareness and gender competence as well. Back in their home organisations, becoming involved in topical discussion, stakeholders themselves are able to raise awareness and widen the understanding of gender bias as a factor in grant allocation in their organisational context.

The GRANteD Stakeholder Committee as an actor for co-creation

Currently, five RFOs are involved in the research of the GRANteD project. These RFOs had to be recruited in the early stage of the project. Due to Covid19 pandemic and other priorities, the recruitment of the intended five RFOs took longer than planed which impacted also the forming of the StC. To be involved in the GRANTeD project, the first step for the RFOs was to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU). The MoU defines the rules for this research collaboration. A core element of the MoU is the provision and protection of data generated in the funding process. A second layer of involvement is to participate in the GRANteD StC. The StC includes all RFOs, which have signed a MoU, but also other RFOs which have shown interest. In addition, some relevant umbrella organisations participate in the StC. If you are interested, you can find all members on the GRANteD website.

Before the Covid19 pandemic, the StC members have met face-to-face; since 2020, the workshops are organised virtually. The members of the StC engaged in discussing the best format, and they agreed on short and topic-specific meetings to be set up.

In the StC work program it was outlined, that the StC is set up for mutual learning and enhancing our research design by enabling transdisciplinary dialogues and developing thematic knowledge collectively. Mutual learning, exchanging experiences on specific topics and sharing good practices, getting to know the most recent discourses and raising questions from daily practice should be on the agenda of the StC meetings. All these insights could be of relevance for RFOs for their (gender equality) policy design.

Here are examples how co-creation was practiced:

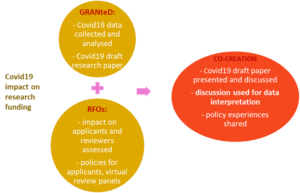

As the Covid19 pandemic emerged in the runtime of the GRANteD project, we have integrated a few questions on the impact of the pandemic on gender in research funding in the interviews with panel members and RFO staff. We analysed data on this for the first RFO and developed a draft paper on the impact of virtual panels for gender equitable grant allocation. RFOs clearly indicated a need to share experiences between RFOs about good practices and implemented measures. While RFOs shared their experiences, the GRANteD consortium could also present some first preliminary findings from the analysis of research data. This enriched the discussion between RFOs. The overall discussion at the end was concerned with the question, whether virtual panels are more or less gender fair than face-to-face panels.

When involving the different stakeholder groups, we ask the following question: Should all stakeholders be engaged in the same way (advanced vs. starter, members with less or more organisational support, members withdifferent power position etc.)? We try to take into account the heterogeneity of the members and turn that into a fruitful resource for co-creation on two levels: Firstly, they co-create the GRANteD research design, as all RFO members have the chance to pick up (tailored) questions for our research design and data collection. Secondly, they co-create the collaboration within the GRANteD StC by voting for specific topics to be discussed. In order to meet the current needs of StC members, they were asked to select the most interesting topics for the StC meetings from a list of suggestions. When the agenda is set, members may be asked what they aim to explore more in depth. An illustrative example for the different layers of co-creating is the work of RFOs on Gender Equality Plans (GEPs).

-

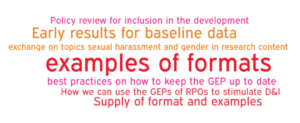

- In the last meeting in January 2022, the topic of Gender Equality Plans (GEPs) for RFOs was selected, according to an earlier vote of the StC members.

- When sending the invitation email, participants were asked to respond to a short survey to specify the content to be discussed in breakout rooms, in order to match partners with shared interests.

- In the warm-up round at the beginning of the meeting, each member could enter in an interactive format (slido) how they expect the GRANteD project to support the GEP development, and this way co-created the further collaboration. Entries are summerized in the word-cloud below (for the question: How can GRANteD support your GEP design)?

Sum-up

So far, we see co-creation as a successful and relevant instrument for stakeholder involvement, shifting beyond simply measuring outputs (number of workshops, number of stakeholders who attend workshops,) to a method that embraces learning and mutual consultation in order to better understand the risks and challenges for gender equality policies in RFOs. This follows very closely the emerging interests and needs for discussion indicated by the members of the StC.

RFOs deliver inputs for the data collection instruments to be developed in the GRANteD project and started reflecting first research findings in the light of their experiences as practitioners. They bring in very different perspectives, as members represent a variety of (science) cultures, different positions within RFOs as well as different levels of gender awareness.

We see the co-creative approach beneficial in two ways: it enables RFOs to share and discuss topics between them, and it enables us researchers to learn about their activities, challenges, and priorities, and to integrate them directly into our research agenda. This way co-creation is relevant for enhancing the collaboration and exchange between stakeholders as well as for enriching the research process and knowledge production. At the end of the GRANteD project, we hope to have better research results and more gender awareness in funding organisations.

References

Caleo, S., Heilman, M. E. (2019): What could go wrong? Some unintended consequences of gender bias interventions. Archives of Scientific Psychology, 7(1), pp. 71-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/arc0000063

Callerstig, A.-C. (2014): Making Equality Work: Ambiguities, Conflicts and Change Agents in the Implementation of Equality Policies in Public Sector Organisations, Doctoral dissertation. Linköping, Linköping University

Carey, G., Dickinson, H., Olney, S. (2019): What can feminist theory offer policy implementation challenges? Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, Volume 15, 2019, pp. 143-159(17). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1332/174426417X14881935664929

Cruz-Castro, L., Echevarria I., Sanz-Menendez, L. (2019): Research Funding Organisations mapping, GRANteD Deliverable 1.2

European Commission (2009): The Gender Challenge in Research Funding. European Commission, Brussels

European Commission (2017): Implicit gender biases during evaluations. How to raise awareness and change attitudes. Workshop report, 30-31 May 201. European Commission, Brussels

Husu, L., Peterson, H. (2022): Synthesis report on contextual factors, gender equality policy analysis and gender bias risk analysis, GRANteD Deliverable D5.1

Loveridge, D., Saritas, O. (2009): Reducing the democratic deficit in institutional foresight programmes: A case for critical systems thinking in nanotechnology, Technological Forecasting & Social Change 76, pp. 1208–1221

Madera, J.M., Hebl, M.R., Dial, H., Martin, R., Valian, V. (2018): “Raising Doubt in Letters of Recommendation for Academia: Gender Differences and Their Impact”, Journal of Business and Psychology, Vol 34, pp. 287–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9541-1

Metz, A., Boaz, A., Robert, G. (2019): Co-creative approaches to knowledge production: what next for bridging the research to practice gap? Evidence & Policy, Volume 15, number 3, pp. 331–337. DOI: 10.1332/174426419X15623193264226

Van den Besselaar, P., Sandström, U., Schiffbänker, H. (2018): “Studying grant decision-making: a linguistic analysis of review reports”, Scientometrics, Volume 117, pp. 313–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2848-x

Van den Brink, M., Benschop, Y. (2012): Gender practices in the construction of academic excellence: Sheep with five legs. Organisation, 19(4), pp. 507-524

Van den Brink, M. (2021): Reinventing the wheel, over and over again”. Organizational learning, memory and forgetting in doing diversity work, in Development and Learning in Organizations, January 2021, DOI: 10.1108/DLO-11-2020-0219

Wennerås, C., Wold, A. (1997): Nepotism and sexism in peer-review. Nature 387, pp. 341–343, May 1997, pmid:9163412